Pocket gophers are burrowing rodents that get their name from their fur-lined cheek pouches, or pockets. These pockets are used, like a squirrel’s, for carrying food. However, the pockets on a gopher open on the outside and turn inside out for emptying and cleaning.

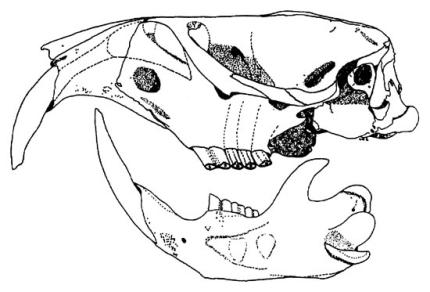

Pocket gophers are well-equipped for a digging, tunneling lifestyle, with large-clawed front paws, small eyes and ears, and sensitive whiskers that assist with movement in the dark. Their pliable fur and sparsely haired tails—which also serve as a sensory mechanism—help gophers run backward almost as fast as they can run forward. Their large front teeth are used to loosen soil and rocks while digging, as well as to cut roots. The pocket gopher’s short fur is a rich brown or yellowish brown, but also may be grayish or closely resemble the local soil color.

Facts about Washington pocket gophers

Food and Feeding Habits

- Unlike moles, which mostly eat insects and other invertebrates, pocket gophers only eat vegetation.

- Gophers eat roots, bulbs, and other fleshy portions of plants they encounter while digging underground.

- Gophers also eat the leaves and stems of plants around their tunnel entrances and can pull entire plants into their tunnels.

- In areas with a snowpack, gophers will gnaw on bark several feet up a tree or shrub.

- Because gophers obtain sufficient moisture from their food, they don’t need a source of open water.

Reproduction and Social Structure

- Pocket gophers breed from early spring to early summer, resulting in one litter of three to seven young per year.

- The nest chamber is located in the pocket gopher’s burrow system, is about 10 inches in diameter, and is lined with dried vegetation.

- The young develop quickly, remain in the nest for five to six weeks, and then wander off above ground to form their own territories.

- Pocket gophers are solitary except during the breeding season or when females have young with them.

- Densities of northern pocket gophers have been found to range from 2 to 20 gophers per acre, depending on food availability, species, and ages of the gophers.

Mortality and Longevity

- Coyotes, domestic dogs and cats, foxes, and bobcats capture gophers at their burrow entrances; badgers, long-tailed weasels, skunks, rattlesnakes, and gopher snakes corner gophers in their burrows. Owls and hawks capture gophers above ground.

- A deep snowpack can result in high gopher mortality. If the snow melts rapidly it saturates the ground and floods the burrows.

- Pocket gophers live one to two years and the majority of the population consists of young adults.

Benefits of Pocket Gophers

A typical pocket gopher can move approximately a ton of soil to the surface each year. This enormous achievement reflects the gopher’s important ecological function.

Their tunnels are built and extended, then gradually fill up with soil as they are abandoned. The old nests, toilets, and partially filled pantries are buried well below the surface where the buried vegetation and droppings become deep fertilization. The soil thus becomes mellow and porous after being penetrated with burrows. Soil that has been compacted by trampling, grazing, and machinery is particularly benefited by the tunneling process.

In mountainous areas, snowmelt and rainfall are temporarily held in gopher burrows instead of running over the surface, where they are likely to cause soil erosion.

Surface mounds created by gophers also bury vegetation deeper and deeper, increasing soil quality over time. In addition, fresh soil in the mounds provides a fresh seedbed for new plants, which may help to increase the variety of plants on a site.

Many mammals, large birds, and snakes eat gophers and depend on their activities to create suitable living conditions. Salamanders, toads, and other creatures seeking cool, moist conditions take refuge in unoccupied gopher burrows. Lizards use abandoned gopher burrows for quick escape cover.

Common pocket gophers of Washington

Two types of pocket gophers occur in Washington: the Western and Northern, with the Western pocket gopher having several subspecies. The Northern pocket gopher (Thomomys talpoides)(Fig. 1) is the smallest and most widespread, occupying much of eastern Washington. Adults of this species measure 8 inches in length, including their 2-inch tail.

The Mazama (Western) pocket gopher (Thomomys mazama) is the only pocket gopher in most of western Washington, with several subspecies ranging from the Olympic Peninsula to the southern Puget Sound area. Adults measure 8 inches in length, including their 2½-inch tail. Sub species in these regions are listed as follows:

Viewing pocket gophers

Although pocket gophers are active year-round and at all hours of the day, their underground lifestyle makes them difficult to observe.

If you are patient, you may be able to watch a pocket gopher feed above ground, or see their food being taken underground. The Mazama pocket gopher spends the most amount of time above ground, generally at night and on overcast days.

When sitting in a grassy area, keep your eyes and ears alert for the sight and sound of a wiggling clump of grass, wild flowers, or similar vegetation. You might see the entire plant slowly disappear below ground, and a few minutes later, the same gopher may venture a body length’s distance from its tunnel opening to alertly feed or gather food.

When gathering food above ground, a pocket gopher will cut vegetation quickly, cram as much as possible into its external pouches (or pockets), and then disappear below ground. It may reappear in a few minutes, gather more food, and disappear to consume the food underground or store it away for later.

Pocket gophers live in extensive burrow systems, which they use for locating food, rearing young, storing food and droppings, and escaping predators. Burrow systems are a closely regulated microenvironment, and gophers will plug any openings in the system within 24 hours. Evidence of a gopher’s burrow system includes mounds, soil plugs, and winter soil casts.

Mounds

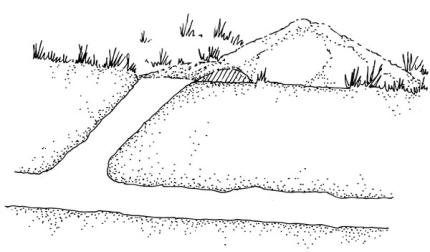

As a pocket gopher tunnels, it loosens soil with its front legs. When digging becomes difficult, it bites off chunks of earth or roots with its incisors. The gopher then somersaults to turn around and push the loose earth and other debris to the surface bulldozer style, with its front feet and head. The excavated material is pushed out of the exit tunnel to the front, right and left, creating a fan-shaped or heart-shaped mound (Fig. 2).

The capacity of pocket gophers to excavate tunnels is phenomenal and heavy clay soil doesn’t deter them. Gophers may create several mounds per day, especially during the seasons when the soil is moist and easy to dig. In irrigated areas such as lawns, gardens, and pastures, digging conditions may be optimal year-round, and mounds can appear at any time.

Tunnels

Pocket gopher tunnels are 1¾ to 3½ inches in diameter, depending on the size of the gopher digging the tunnel. Tunnels occur 4 to 12 inches below ground, whereas the nest and food storage chamber may be as deep as 6 feet. Tunnels tend to be deeper in drier soils. Short, sloping, lateral tunnels connect the main tunnel system to the surface and are created for pushing dirt to the surface and access to foraging on the surface (Fig. 3).

Soil Plugs

Tunnel exits made by a pocket gopher are marked by a 1- to 3 inch circle of disturbed soil, or a circular depression, called a “soil plug.” Soil plugs occur where a gopher emerged to forage or deposit soil, and then plugged up the hole on reentry. Plugs are found at mounds or along the course of the burrow system. Vegetation may be clipped around the soil plugs where a gopher was foraging.

Winter Soil Casts

Soil casts are created because pocket gophers commonly backfill their previously excavated tunnels with excess soil when they dig new tunnels. Casts are the result of this excess soil being backfilled into snow tunnels. When the snow melts, these then become apparent. Castings are nearly always fragmented and in short sections. Only a fraction of snow tunnels are backfilled with soil, so castings represent only a fraction of the gopher’s winter work.

Preventing conflicts

The ecological services of pocket gophers, which are substantial, are often not appreciated, particularly when the animals make their presence known by eating garden crops or damaging orchard or ornamental trees.

For homeowners and gardeners, gophers may be only an occasional (or seasonal) nuisance in lawns and garden beds, and not a long-term problem or threat. Where these animals are not so numerous as to be causing heavy damage, they should be considered neutral.

The subspecies Brush Prairie pocket gopher and the Mazama (Western) pocket gopher are of conservation concern (see "Legal Status" and "Mazama Pocket Gopher Conservation"). The presence of one of these species in an area where you plan to take action—chemical, nonchemical, mechanical, or otherwise—could preclude use of this action. Before moving forward with any type of control, contact your local Fish and Wildlife office.

The following are suggestions for reducing conflicts. In cases where these methods are not practical, contact your local County Extension Agent or local Fish and Wildlife office for further information.

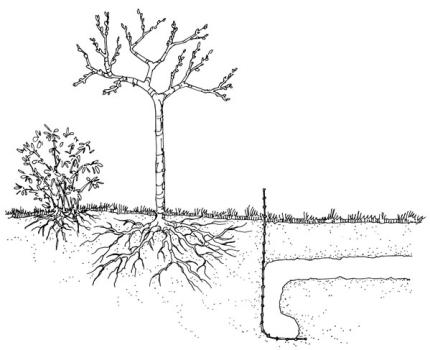

Barriers: Constructing a barrier to keep pocket gophers from tunneling into an area can be labor-intensive and costly; however, this approach is recommended for small areas and areas containing valuable plants. Flowerbeds and nursery beds can be protected by complete underground screening of the sides and bottom. Raised beds with rock or wooden side supports will only require bottom protection (Fig. 4).

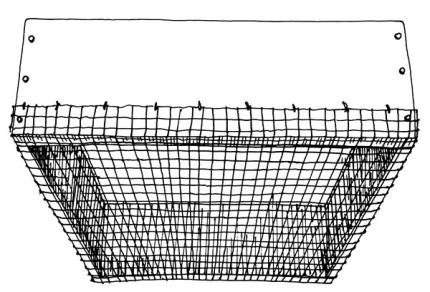

Wire baskets can be used to protect the roots of individual trees and shrubs. These can be purchased from nurseries or farm supply centers, or be homemade. Use a double layer of light-gauge wire, such as 1-inch mesh chicken wire for trees and shrubs that will need protection only while young. Leave enough room to allow for a few years of root development before the wire rots away.

Groups of bulbs (gophers are reported not to eat daffodil bulbs) and other plants needing long-term protection can be placed in baskets made from ½-inch mesh hardware cloth, available from hardware stores and building supply centers.

Large areas, such as vegetable gardens, can be protected using an underground gopher fence (Fig. 5) or a stone-filled trench. However, such a below-ground barrier will only slow the movements of gophers for a time; sooner or later the barrier will be breached since gophers are capable of digging much deeper than 24 inches.

To add to the life of underground barriers, spray on two coats of rustproof paint before installation. Above-ground parts can also be painted to blend in. Always check for utility lines before digging in an area.

Several types of barriers (plastic tubes, one gallon plant containers) are effective at protecting aboveground parts of small plants, such as newly planted conifers.

Gophers may be deterred from chewing underground sprinkler lines or utility cables by surrounding them with 6 to 8 inches of coarse gravel 1 inch or more in diameter.

Legal Status

The subspecies Brush Prairie pocket gopher (Thomomys talpoides douglasi) of Clark County may be extinct. The Mazama (Western) pocket gopher (Thomomys mazama) of Thurston, Pierce, Clark, and Mason Counties is state threatened and the subspecies in Thurston and Pierce counties were listed as Threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act in April 2014. Because only remnant populations of these subspecies and species exist, people are not permitted to use lethal control in these areas.

Elsewhere, pocket gophers are unclassified and may be trapped or killed and no special trapping permit is necessary for the use of live traps. However, a special trapping permit is required for the use of all traps other than live traps (RCW 77.15.192, 77.15.194; WAC 232-12-142). There are no exceptions for emergencies and no provisions for verbal approval. All special trapping permit applications must be in writing on a form available from the Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW)

It is unlawful to release a pocket gopher anywhere within the state, other than on the property where it was legally trapped, without a permit to do so (RCW 77.15.250; WAC 220-450-010).

Because legal status, trapping restrictions, and other information about gophers change, contact your local WDFW office for updates.

Mazama Pocket Gopher Conservation

In the south Puget Sound area, many populations of Mazama pocket gopher have disappeared since the 1940s .

Mazama pocket gophers continue to decline in numbers in part because of their small, local breeding populations. For many years the species has persisted by continually recolonizing areas after local extinctions have occurred; however, loss of habitat to development, trapping by homeowners, and persecution by domestic cats and dogs have probably stopped much of this recolonization.

While large populations of some pocket gopher species can recover, the small and isolated populations of the Mazama pocket gopher can be completely lost.

If Mazama pocket gophers are to persist in the south Puget Sound area, they will require protection and lands where management is compatible with their needs. In addition, because Mazama gophers occupy grassy areas near homes and private property, a heightened level of tolerance will be required from those people who share their territories. In addition, if gophers are to survive in the suburbs, it may only be because homeowners are willing to keep their cats indoors.

The last records of Tacoma pocket gophers, T.m. tacomensis may have been individuals reported by residents to have been killed by domestic cats .

Public Health Concerns

Gophers are not considered to be a significant source of any infectious disease transmittable to humans or domestic animals.

Additional information

Books

Hygnstrom, Scott E., et al. Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources, 1994. (Available from: University of Nebraska Cooperative Extension, 202 Natural Resources Hall, Lincoln, NE 68583-0819; phone: 402-472-2188; also see Internet Site below.)

Maser, Chris. Mammals of the Pacific Northwest: From the Coast to the High Cascades. Corvalis: Oregon State University Press, 1998.

Verts, B. J., and Leslie N. Carraway. Land Mammals of Oregon. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1998.

Internet Resources