Skunks are mild-tempered, mostly nocturnal, and will defend themselves only when cornered or attacked. Even when other animals or people are in close proximity, skunks will ignore the intruders unless they are disturbed.

Skunks are beneficial to farmers, gardeners, and landowners because they feed on large numbers of agricultural and garden pests. While young skunks are cute and kitten-like, they are wild animals and it is illegal to keep them as pets.

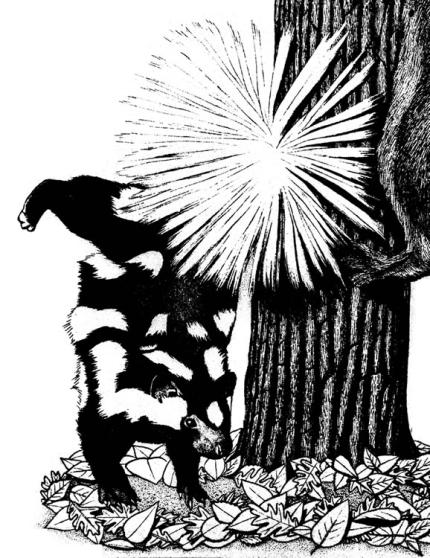

Two skunk species live in Washington: The Striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis)(Fig. 1) is the size of a domestic cat, ranging in length from 22 to 32 inches, including its tail. Its fur is jet black except for two prominent white stripes running down its back. The striped skunk occurs throughout most lowland areas in Washington, preferring open fields, pastures, and croplands near brushy fencerows, rock outcroppings, and brushy draws. It is also seen—or its musky odor noticed—in some suburban and urban locations, particularly near sources of open water.

The Spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius), also known as the polecat, ranges in length from 14 to 18 inches, including its tail. Its fur is a black or grayish black, with white stripes on its shoulders and sides, and white spots on its forehead, cheeks, and rump.

The spotted skunk occurs throughout west and southeast Washington. The spotted skunk and striped skunk use similar types of habitat, although the spotted skunk is more likely to be seen in and around forests and woodlands, and is not as tolerant of human activity as the striped skunk

Facts about Washington skunks

Food and Feeding Habits

- Skunks will eat what they can find or catch. They have large feet, well-developed claws, and digging is their primary method used to obtain food.

- Some of their favorite foods include, mice, moles, voles, rats, birds and their eggs, and carcasses—also grasshoppers, wasps, bees, crickets, beetles, and beetle larvae.

- Skunks also eat fruits, nuts, garden crops, and scavenge on garbage, birdseed, and pet food.

- Skunks will roll caterpillars on the ground to remove the hairs before eating them. They will also roll beetles that emit a defensive scent, causing the beetle to deplete its scent before they eat it.

Den Sites

- Skunks use underground dens year-round for daytime resting, hiding, birthing and rearing young.

- Dens are located under wood and rock piles, buildings, porches, and concrete slabs—also in rock crevices, culverts, drainpipes, and in standing or fallen hollow trees.

- Skunks may dig their own dens, but more often use the deserted burrows of other animals, such as ground squirrels and marmots.

- Dens are either permanent, or used alternately with other dens.

- Spotted skunks are excellent climbers and may use an attic or a hayloft as a den.

- Skunks do not hibernate; instead, they lower their body temperature and stay inside their dens during extreme cold, plugging the entrance with leaves and grass to insulate them from the cold.

- Female skunks sometimes share communal dens.

Reproduction

- Striped skunks breed from February through March. Spotted skunks breed from September through October and experience delayed implantation; the fertilized egg does not attach to the uterine wall for a period of time after breeding.

- In late April and May, females of both species give birth to four to five young in an underground nest lined with dried grass and other vegetation.

- At around 60 days of age, the mother leads her young out at dusk to forage and hunt. At three months old the skunks are almost full-grown and completely independent.

- Striped skunk families often remain together throughout the winter.

Mortality and Longevity

- Skunks have few predators—hungry coyotes, foxes, bobcats, and cougars, also large owls (which have little sense of smell). Domestic dogs will also kill skunks.

- Skunks also die as a result of road kills, trapping, shooting, and killing by farm chemicals and machinery.

- Striped skunks live three to four years in the wild; spotted skunks live half that long.

Viewing skunks

Signs of Skunks

Signs of skunks include their tracks, droppings, and evidence of their digging. A musky odor is another sign of their presence. A persistent smell and freshly excavated soil next to a hole under a building or woodpile indicates that a skunk may have taken up residence.

Skunks usually begin foraging after dark and are back in their dens before daylight. While striped skunks are sometimes seen during the day, spotted skunks seldom are—they may not even venture out on bright moonlit nights.

Skunks search for food along established routes and have a home range of less than 2 miles. Since they commonly patrol country roads looking for road-killed animals, vehicles often hit them.

When around skunks, avoid making loud noises, moving quickly, or taking other steps that could be interpreted by the skunk as a threat. If the skunk appears agitated, retreat quietly and slowly.

Skunks have poor eyesight and will often approach people who are standing still. If this happens, slowly move away from the approaching skunk.

Tracks

Skunk tracks can be found in mud, dirt, or snow around den sites and feeding areas (Fig. 2). Skunk tracks look like domestic cat prints, except they show claw marks and five toes, not four. Unlike cats, skunks can’t retract their claws, so each of their toe pads has a claw mark in front of it. Skunk tracks are also usually staggered, unlike domestic cat prints, which are often on top of each other.

Droppings

Look for droppings where skunks have been feeding or digging, or near a den. Droppings look like those of domestic cats and contain all types of food, from insect skeletons, to seeds or hair. Striped skunk droppings are ½ inch in diameter, 2 to 4 inches long, and usually have blunt ends. Spotted skunk droppings are similar looking, but half the size.

Getting Skunked

In other animals, musk is used for scent-marking and courtship. Only the skunks have turned musk into olfactory muscle. When an adult skunk or its young are threatened, they may emit a musky fluid from a nozzlelike duct that protrudes from the animal’s anus. This fluid—nature’s version of tear gas—can be discharged either in a fine mist or in a water-pistol-type stream. It has a stifling, pungent, often gagging odor that can persist for weeks and be detected over a mile away. On a still day, a skunk can discharge musk 12 feet with good accuracy. On a windy day, spray may reach a person standing downwind 18 feet away or more. Because even a few droplets of skunk spray smell so strongly, it doesn’t take a direct hit to pick up the odor.

People’s reaction to the odor varies greatly. Almost everyone finds it intolerable when in high concentration. Some people become violently ill. Low levels of the odor are still repugnant to most, while a few find them bearable or almost pleasant.

Because skunks have a limited supply of ammunition, they don’t waste their defensive spray. A striped skunk can fire five to eight times before it has to reload, which takes about a week.

Fortunately skunks have various ways of warning when they are threatened, giving an intruder ample opportunity to back off. Dogs, however, tend to ignore this warning. That’s why it’s hard to find a human who has been sprayed, but easy to find a dog that has!

Contrary to popular myth, a striped skunk cannot spray over its back. When threatened it will stomp its front feet and, if the threat continues, it will make short charges with its tail raised in the direction of the threat. Next, the skunk will twist its hind end around so it is headed in the same direction as its snout. If the sunk continues to feel threatened, it will then spray.

Musk produced by spotted skunks is more pungent than that of striped skunks. However, they are less likely to spray, and will climb a fence post or a tree when threatened. When forced to, a spotted skunk will stand on its front feet with its back arched so that the spray is discharged forward (Fig. 3).

The odor-bearing fluid, or musk, is amber in color, oily, and only slightly volatile. Therefore, it goes away “on its own” very slowly. However, it will go away eventually (perhaps in two to four months), even if nothing is done to get rid of the odor. This natural process is greatly slowed in areas with little ventilation and when the musk has penetrated porous materials.

If a person or pet is sprayed, the quicker you do something about it the more completely you can remove the odor. First, if eyes get irritated, flush them liberally with cold water. Next, because the strong smelling compounds in skunk spray are slightly acidic, counteract them with a highly alkaline laundry soap. This will deodorize the compounds and make them more soluble in water.

Commercial preparations containing “neutroleum alpha,” available from some pet stores, may also be effective.

After washing with any remedy solution, follow with a long hot shower. Depending on the severity of the spray, you may have to repeat the process two or three times.

These solutions may be used to eliminate most of the skunk odor from people and pets. When washing a dog, wash the body first and then the head to keep the dog from shaking off the mixture. This will make the odor tolerable—only time will eliminate it. Never use bleach or ammonia, at any dilution, on pets.

If the clothing has been heavily sprayed, however, your best option may be to discard or burn it, because fabric can hold the skunk odor for a long time.

The above products may also be used to clean odor from inanimate objects. If the odor is inside or under your house, the area will need to be thoroughly aired out. Using fans will help.

And remember . . . the best remedy is Don’t Get Sprayed!

Preventing conflicts

Even though skunks possess a powerful spray defense, they will not spray unless surprised, cornered, harmed, or they need to protect their young. Young skunks are more likely to spray than more experienced skunks.

Occasional skunk sightings in a neighborhood need not be cause for alarm. Because skunks are nomadic, most concerns about them being under sheds, porches, and outbuildings are resolved in due time: skunks just move on.

The most effective way to prevent conflicts is to modify the habitat around your home so as not to attract skunks.

Do not feed skunks.

Doing so may create undesirable situations for you, your children, your pets, and the skunks. Skunks that are artificially fed often lose their fear of humans. Artificial feeding also tends to concentrate skunks in a small area, and overcrowding can encourage diseases or parasites. Finally, these skunks might drop in on neighbors who do not want them around. These same neighbors might decide to have the skunks removed.

In addition, feed dogs or cats inside or clean up any spilled or uneaten food before dark, place indoor pet food or other food away from a pet door, and put food in secure compost containers. Also, regularly clean up bird feeding stations.

Prevent access to denning sites.

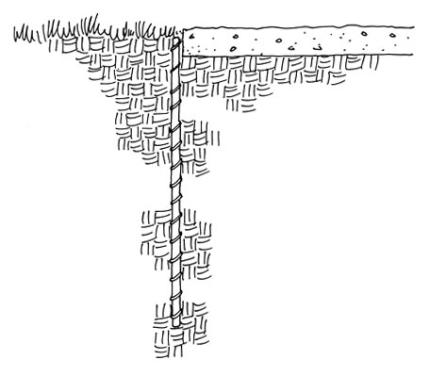

Skunks frequently den under houses, porches, sheds, and similar places. Close off these areas with ¼-inch hardware cloth, boards, metal flashing, or other sturdy barriers. Make all connections flush and secure to keep mice, rats, and other small mammals out. Make sure you don’t trap an animal inside when you seal off a potential entry (see Evicting Animals from Buildings). To prevent skunks from digging under a building or concrete slab, install a barrier (Fig. 4).

Enclose ducks and chickens in a secure coop at night.

A skunk may dig or otherwise find its way into a chicken coop and kill one or two small fowl, but if several chickens or ducks have been killed at one time, the predator is more likely a weasel, mink, fox, raccoon, or bobcat. If a skunk is eating the eggs of chickens or ducks, you will usually find eggs opened on one end with the edges crushed inward. A skunk cannot easily carry or hold chicken-sized eggs; therefore, the eggshells are rarely moved more than 3 feet from the nest.

To prevent skunks from digging under the coop or pen, create a barrier (Fig. 4).

Protect your pets.

To keep pets from being sprayed, keep them inside at night.

Prevent damage to lawns.

Because lawns—especially newly created ones—are often heavily watered, worms and grubs inhabit areas just under the sod, attracting skunks (and raccoons). Skunks tend to dig 1- to 3-inch deep holes only where a grub is located; raccoons tend to roll or shred the sod in their search. The use of pesticides to kill worms and grubs is not recommended because of their toxic effect on the environment, people, and animals.

To prevent digging, lay down 1-inch mesh chicken wire, securing the wire with stakes or heavy stones or heavy objects. Alternatively, sprinkle cayenne pepper or a commercial dog and cat repellent available at most pet stores or garden centers—over small areas during dry weather.

Surrounding the area with a low chicken-wire fence used to prevent rabbit damage can protect large areas from striped skunks. (See "Preventing Conflicts" in Rabbits for a fence design). To prevent spotted skunks from climbing, use the mini floppy fence described under "Preventing Conflicts" in Mountain Beaver.) A temporary, single strand of electric wire 5 inches above the ground will also deter skunks (see "Electric Fences" in Deer).

Skunks in or Under Buildings

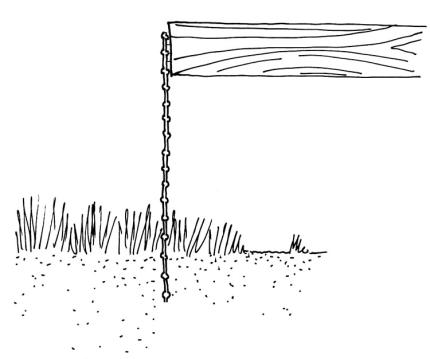

Occasionally a skunk will find a suitable den site in or under a building, gaining access from under a porch or deck (Fig. 5). Skunks normally occupy a den site for only two or three consecutive nights. However, during the mating and nesting season, females are attracted to warm, dry, dark, easily defended areas, and will remain longer if the setting remains favorable.

You may choose to let skunks occupy an area, such as under an outbuilding, if they don’t pose a problem. Should you choose to remove the animals, a wildlife control company can be hired (see Hiring a Wildlife Control Company), or you can complete the process yourself (see Evicting Animals from Buildings.)

If a skunk finds its way into your house, garage, or other structure, stay calm, close all but one outside door, and let the animal find its own way out. If necessary, you can slowly encourage the skunk to move in a preferred direction while holding a large towel, or a large piece of plastic or cardboard in front of you. If the skunk appears agitated, retreat immediately. Don’t use food as a lure—this will make the animal associate food with humans, and return for more. If the skunk appears sick or injured, call a nearby wildlife rehabilitator for assistance (see Wildlife Rehabilitators and Wildlife Rehabilitation for information).

Trapping Skunks

If all efforts to dissuade problem skunks fail, you may feel the need to trap the animals. Trapping skunks should be a last resort and can never be justified without first applying the above-described preventative measures. Trapping is also rarely a permanent solution since other skunks are likely to move into the area if attractive habitat is still available.

A wildlife damage control company can be hired to do the trapping, or you can do it yourself (see Hiring a Wildlife Damage Control Company). It is usually best to let someone with experience trapping skunks do the work. Because skunks often live in groups, multiple traps are necessary to trap them out of an area. If you choose to do the trapping yourself, follow the steps listed in Trapping Wildlife.

Additional Information

Books

Link, Russell. Landscaping for Wildlife in the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: University of Washington Press and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, 1999.

Maser, Chris. Mammals of the Pacific Northwest: From the Coast to the High Cascades. Corvalis: Oregon State University Press, 1998..

Verts, B. J., and Leslie N. Carraway. Land Mammals of Oregon. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1998.

Internet Resources