Raccoons are a common sight in much of Washington, often drawn to urban areas by food supplied by humans. As long as raccoons are kept out of human homes, not cornered, and not treated as pets, they are not dangerous.

Description and Range

Physical description

The raccoon is a native mammal, measuring about 3 feet long, including its 12-inch, bushy, ringed tail. Because their hind legs are longer than the front legs, raccoons have a hunched appearance when they walk or run. Each of their front feet has five dexterous toes, allowing raccoons to grasp and manipulate food and other items.

Adult raccoons weigh 15 to 40 pounds, their weight being a result of genetics, age, available food, and habitat location. Males have weighed in at over 60 pounds. A raccoon in the wild will probably weigh less than the urbanized raccoon that has learned to live on handouts, pet food, and garbage-can leftovers.

Geographic range

Raccoons prefer forest areas near a stream or water source, but have adapted to various environments throughout Washington. Raccoon populations can get quite large in urban areas, owing to hunting and trapping restrictions, few predators, and human-supplied food.

Living with wildlife

Food and feeding habitats

Raccoons will eat almost anything, but are particularly fond of creatures found in water—clams, crayfish, frogs, fish, and snails. Raccoons also eat insects, slugs, dead animals, birds and bird eggs, as well as fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds. Around humans, raccoons often eat garbage and pet food. Although not great hunters, raccoons can catch young gophers, squirrels, mice, and rats. Except during the breeding season and for females with young, raccoons are solitary. Individuals will eat together if a large amount of food is available in an area.

Den sites and resting sites

Dens are used for shelter and raising young. They include abandoned burrows dug by other mammals, areas in or under large rock piles and brush piles, hollow logs, and holes in trees. Den sites also include wood duck nest-boxes, attics, crawl spaces, chimneys, and abandoned vehicles. In urban areas, raccoons normally use den sites as daytime rest sites. In wooded areas, they often rest in trees. Raccoons generally move to different den or daytime rest site every few days and do not follow a predictable pattern. Only a female with young or an animal “holed up” during a cold spell will use the same den for any length of time. Several raccoons may den together during winter storms.

Reproduction and home range

Raccoons pair up only during the breeding season, and mating occurs as early as January to as late as June. The peak mating period is March to April. After a 65-day gestation period, two to three kits are born. The kits remain in the den until they are about seven weeks old, at which time they can walk, run, climb, and begin to occupy alternate dens. At eight to ten weeks of age, the young regularly accompany their mother outside the den and forage for them selves. By 12 weeks, the kits roam on their own for several nights before returning to their mother. The kits remain with their mother in her home range through winter, and in early spring seek out their own territories. The size of a raccoon’s home range as well as its nightly hunting area varies greatly depending on the habitat and food supply. Home range diameters of 1 mile are known to occur in urban areas.

Mortality and longevity

Raccoons die from encounters with vehicles, hunters, and trappers, and from disease, starvation, and predation. Young raccoons are the main victims of starvation, since they have very little fat reserves to draw from during food shortages in late winter and early spring. Raccoon predators include cougars, bobcats, coyotes, and domestic dogs. Large owls and eagles will prey on young raccoons. The average life span of a raccoon in the wild is 2 to 3 years; captive raccoons have lived 13.

Viewing raccoons

Raccoons can be seen throughout the year, except during extremely cold periods. Usually observed at night, they are occasionally seen during the day eating or napping in a tree or searching elsewhere for food. Coastal raccoons take advantage of low tides and are seen foraging on shellfish and other food by day.

Trails

Raccoons use trails made by other wildlife or humans next to creeks, ravines, ponds, and other water sources. Raccoons often use culverts as a safe way to cross under roads. With a marsh on one side of the road and woods on the other, a culvert becomes their chief route back and forth. Look for raccoon tracks in sand, mud, or soft soil at either end of the culvert.

In developed areas, raccoon travel along fences, next to buildings, and near food sources.

Tracks, scratch marks, and similar signs

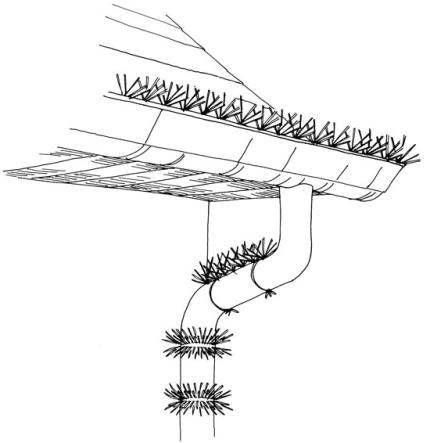

Look for tracks in sand, mud, or soft soil, also on deck railings, fire escapes, and other surfaces that raccoons use to gain access to structures. Tracks may appear as smudge marks on the side of a house where a raccoon shimmies up and down a downspout or utility pipe.

Sharp, nonretractable claws and long digits make raccoons good climbers. Like squirrels, raccoons can rotate their hind feet 180 degrees and descend trees headfirst. (Cats’ claws don’t rotate and they have to back down trees.) Look for scratch marks on trees and other structures that raccoons climb.

Look for wear marks, body oil, and hairs on wood and other rough surfaces, particularly around the edges of den entrances. The den’s entrance hole is usually at least 4 inches high and 6 inches wide.

Droppings

Raccoon droppings are crumbly, flat-ended, and can contain a variety of food items. The length is 3 to 5 inches, but this is usually broken into segments. The diameter is about the size of the end of your little finger.

Raccoons leave droppings on logs, at the base of trees, and on roofs (raccoons defecate before climbing trees and entering structures). Raccoons create toilet areas—inside and outside structures—away from the nesting area. House cats have similar habits.

Note: Raccoon droppings may carry a parasite that can be fatal to humans. Do not handle or smell raccoon droppings and wash your hands if you touch any.

Calls

Raccoons make several types of noises, including a purr, a chittering sound, and various growls, snarls, and snorts.

Legal status

Because legal status, trapping restrictions, and other information about raccoons change, contact your WDFW Regional Office for updates.

The raccoon is classified as both a furbearer and a game animal . A hunting or trapping license is required to hunt or trap raccoons during an open season. A property owner or the owner’s immediate family, employee, or tenant may kill or trap a raccoon on that property if it is damaging crops or domestic animals. In such cases, no permit is necessary for the use of live (cage) traps. However, a special trapping permit is required for the use of all traps other than live traps (RCW 77.15.192, 77.15.194).

It is unlawful to release wildlife anywhere within the state, other than on the property where it was legally trapped, without a permit to do so (RCW 77.15.250). Except for bona fide public or private zoological parks, persons and entities are prohibited from importing raccoons into Washington State without a permit to do so.

Preventing conflict

A raccoon’s search for food may lead it to a vegetable garden, fish pond, garbage can, or chicken coop. Its search for a den site may lead it to an attic, chimney, or crawl space. Sometimes, you may need to evict a raccoon or other animal from a building.

The most effective way to prevent conflicts is to modify the habitat around your home so as not to attract raccoons. Recommendations on how to do this are given below:

Don’t feed raccoons: Feeding raccoons may create undesirable situations for you, your children, neighbors, pets, and the raccoons themselves. Raccoons that are fed by people often lose their fear of humans and may become aggressive when not fed as expected. Artificial feeding also tends to concentrate raccoons in a small area; overcrowding can spread diseases and parasites. Finally, these hungry visitors might approach a neighbor who doesn’t share your appreciation of the animals. The neighbor might choose to remove these raccoons, or have them removed.

Don’t give raccoons access to garbage: Keep your garbage can lid on tight by securing it with rope, chain, bungee cords, or weights. Better yet, buy garbage cans with clamps or other mechanisms that hold lids on. To prevent tipping, secure side handles to metal or wooden stakes driven into the ground. Or keep your cans in tight-fitting bins, a shed, or a garage. Put garbage cans out for pickup in the morning, after raccoons have returned to their resting areas.

Feed dogs and cats indoors and keep them in at night: If you must feed your pets outside, do so in late morning or at midday, and pick up food, water bowls, leftovers, and spilled food well before dark every day.

Keep pets indoors at night: If cornered, raccoons may attack dogs and cats. Bite wounds from raccoons can result in fractures and disease transmission.

Prevent raccoons from entering pet doors: Keep indoor pet food and any other food away from a pet door. Lock the pet door at night. If it is necessary to have it remain open, put an electronically activated opener on your pet’s collar. Note: Floodlights or motion detector lights placed above the pet door to scare raccoons are not long-term solutions.

Put food in secure compost containers and clean up barbecue areas: Don’t put food of any kind in open compost piles; instead, use a securely covered compost structure or a commercially available raccoon-proof composter to prevent attracting raccoons and getting exposed to their droppings. A covered worm box is another alternative. If burying food scraps, cover them with at least 8 inches of soil and don’t leave any garbage above ground in the area—including the stinky shovel. Placing a wire mesh barrier that is held in place with a heavy object over the in-ground compost will prevent problems. Clean barbecue grills and grease traps thoroughly following each use.

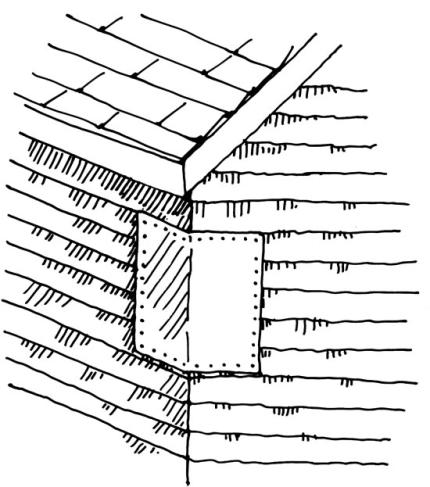

Eliminate access to denning sites: Raccoons commonly use chimneys, attics, and spaces under houses, porches, and sheds as den sites. Close any potential entries with ¼-inch mesh hardware cloth, boards, or metal flashing. Make all connections flush and secure to keep mice, rats, and other mammals out. Make sure you don’t trap an animal inside when you seal off a potential entry.

Prevent raccoons from accessing rooftops by trimming tree limbs away from structures and by attaching sheets of metal flashing around corners of buildings. Commercial products that prevent climbing are available from farm supply centers and online from bird-control supply companies. Remove vegetation on buildings, such as English ivy, which provide raccoons a way to climb structures and hide their access point inside.

Enclose poultry (chickens, ducks, and turkeys) in a secure outdoor pen and house: Raccoons will eat poultry and their eggs if they can get to them. Signs of raccoon predation include the birds’ heads bitten off and left some distance away, only the bird’s crop being eaten, stuck birds pulled half-way through a fence, and nests in severe disarray. Note: Other killers of poultry include coyotes, foxes, skunks, feral cats, dogs, bobcats, opossums, weasels, eagles, hawks, owls, other poultry, and disease.

If a dead bird is found with no apparent injuries, skinning it may determine what killed it. If the carcass is patterned by red spots where pointed teeth have bruised the flesh but not broken the skin, the bird was probably “played with” by one or more dogs until it died.

To prevent raccoons and other animals from accessing birds in their night roosts, equip poultry houses with well-fitted doors and secure locking mechanisms. A raccoon’s dexterous paws make it possible for it to open various types of fasteners, latches, and containers.

To prevent raccoons and other animals from accessing poultry during the day, completely enclose outdoor pens with 1-inch chicken wire placed over a sturdy wooden framework. Overlap and securely wire all seams on top to prevent raccoons from forcing their way in by using their weight and claws. To prevent raccoons from reaching in at ground level, surround the bottom 18 inches of the pen with smaller-mesh wire.

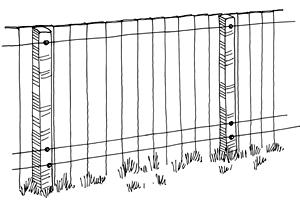

Fence orchards and vegetable gardens: Raccoons can easily climb wood or wire fences, or bypass them by using overhanging limbs of trees or shrubs. Wire fences will need to have a mesh size that is no wider than 3 inches to keep young raccoons out.

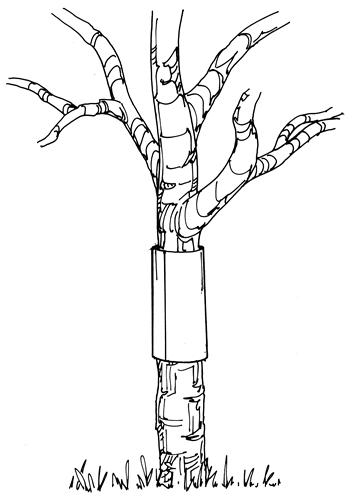

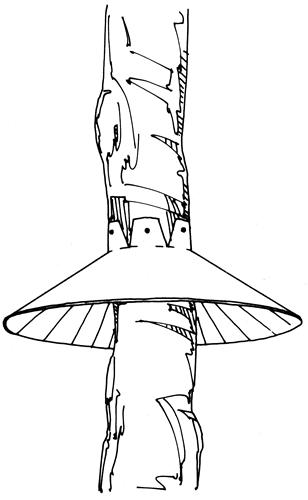

Protect fruit trees, bird feeders, and nest boxes: To prevent raccoons from climbing fruit trees, poles, and other vertical structures, install a metal or heavy plastic barrier. Twenty-four-inch long aluminum or galvanized vent-pipe, available at most hardware stores, can serve as a premade barrier around a narrow support. Note: Raccoons will attempt to use surrounding trees or structures as an avenue to access the area above the barrier.

Alternatively, a funnel-shaped piece of aluminum flashing can be fitted around the tree or other vertical structure. The outside edge of the flared metal should be a minimum of 18 inches away from the support. Cut the material with tin snips and file down any sharp edges.

Trapping Raccoons

Trapping and relocating a raccoon several miles away seems an appealing method of resolving a conflict because it is perceived as giving the “problem animal” a second chance in a new home. Unfortunately, the reality of the situation is quite different. Raccoons typically try to return to their original territories, often getting hit by a car or killed by a predator in the process. If they remain in the new area, they may get into fights (oftentimes to the death) with resident raccoons for limited food, shelter, or nesting sites. Raccoons may also transmit diseases to rural populations that they have picked up from urban pets. Finally, if a place “in the wild” or an urban green space is perfect for raccoons, raccoons are probably already there. It isn’t fair to the animals already living there to release another competitor into their home range.

Raccoons used to a particular food source, type of shelter, or human activity will seek out familiar situations and surroundings. People, organizations, or agencies that illegally move raccoons should be willing to assume liability for any damages or injuries caused by these animals. Precisely for these reasons, raccoons posing a threat to human and pet safety should not be relocated.

In many cases, moving raccoons will not solve the original problem because other raccoons will replace them and cause similar conflicts. Hence, it is more effective to make the site less attractive to raccoons than it is to routinely trap them.

Trapping also may not be legal in some urban areas; check with local authorities. Transporting animals without the proper permit is also unlawful in most cases.

Lethal Control

Lethal control is a last resort and can never be justified without first applying the above-described nonlethal control techniques. Lethal control is rarely a long-term solution since other raccoons are likely to move in if food, water, or shelter remains available.

If all efforts to dissuade a problem raccoon fail, the animal may have to be trapped.

While shooting can be effective in eliminating a single raccoon, it is generally limited to rural situations. Shooting is considered too hazardous in more populated areas, even if legal.

Public Health Concerns

A disease that contributes significantly to raccoon mortality is canine distemper. Canine distemper is also a common disease fatal to domestic dogs, foxes, coyotes, mink, otters, weasels, and skunks. It is caused by a virus and is spread most often when animals come in contact with the bodily secretions of animals infected with the disease. Gloves, cages, and other objects that have come in contact with infected animals can also contain the virus. The best prevention against canine distemper is to have your dogs vaccinated and kept away from raccoons.

Raccoons in Washington often have roundworms (like domestic dogs and cats do, but from a different worm). Raccoon roundworm does not usually cause a serious problem for raccoons. However, roundworm eggs shed in raccoon droppings can cause mild to serious illness in other animals and humans. Although rarely documented anywhere in the United States, raccoon roundworm can infect a person who accidentally ingests or inhales the parasite’s eggs.

Prevention consists of never touching or inhaling raccoon droppings, using rubber gloves and a mask when cleaning areas (including traps) that have been occupied by raccoons, and keeping young children and pets away from areas where raccoons concentrate. (If washing raccoon droppings from a roof, watch where the liquid matter is going.) Routinely encourage or assist your children to wash their hands after playing outdoors. Unfortunately, raccoon roundworm eggs can remain alive in soil and other places for several months.

If a person is bitten or scratched by a raccoon, immediately scrub the wound with soap and water. Flush the wound liberally with tap water. In other parts of the United States raccoons can carry rabies. Contact your physician and the local health department immediately. If your pet is bitten, follow the same cleansing procedure and contact your veterinarian.